“(In Duccio) the common life is transfigured into the uncommon life of a spiritual event” —John W. Dixon, Jr., “Painting as Theological Thought: Issues in Tuscan Theology” in Art, Creativity and the Sacred, Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, ed.

In his essay, “Painting as Theological Thought: Issues in Tuscan Theology,” John Dixon compares the sensitivity of gesture in the work of Giotto di Bondone and Duccio di Buoninsegna. Looking at the figures of Duccio di Buoninsegna’s Maestà, an altar piece commissioned by the city of Siena in 1308, Dixon suggests that although Duccio is commonly categorized as an Italian painter closest to the Byzantine style, it is important to go beyond this cliché to discover a sense of the theological message Duccio’s work conveys.

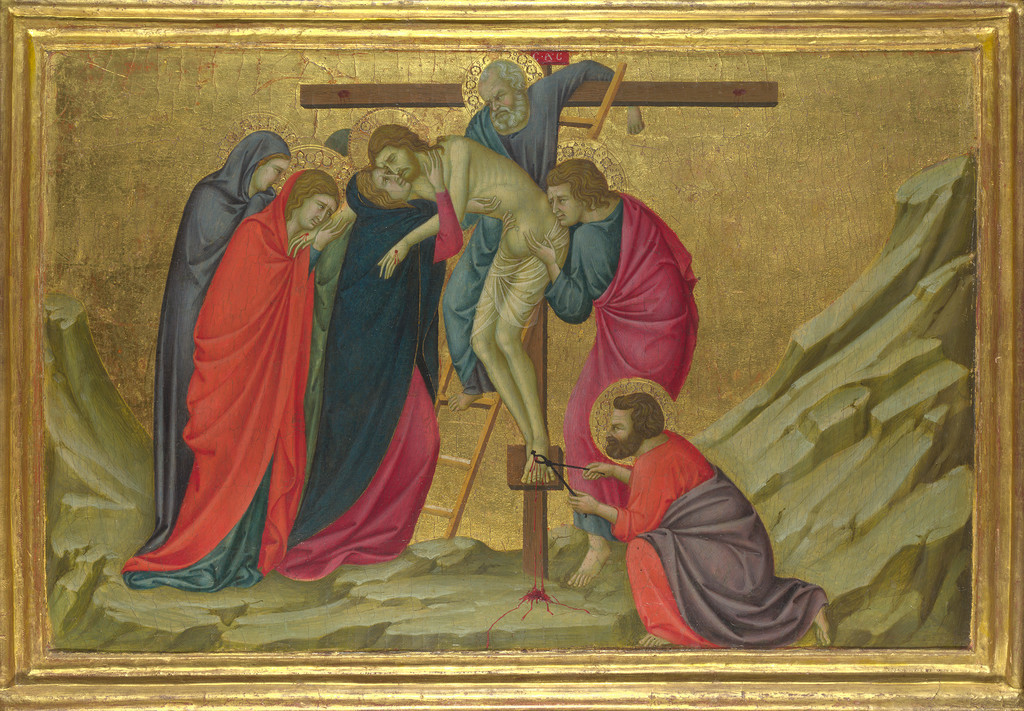

“Duccio’s gesture is every bit as precise, every bit as revealing (as Giotto’s). Judas avidly grasps after the money and the whole group huddles conspiratorially, the only such congestion of a group on the whole Maestà. Or Joseph braces himself on the ladder while he holds the limp dead body that falls from the sorrowful emptiness above the cross. Yet it is perfectly evident that Giotto and Duccio differed in their handling of the figures making these gestures, and in that difference lies the clue to their differing purposes and the seeds of the further development of theological work in Tuscany.”

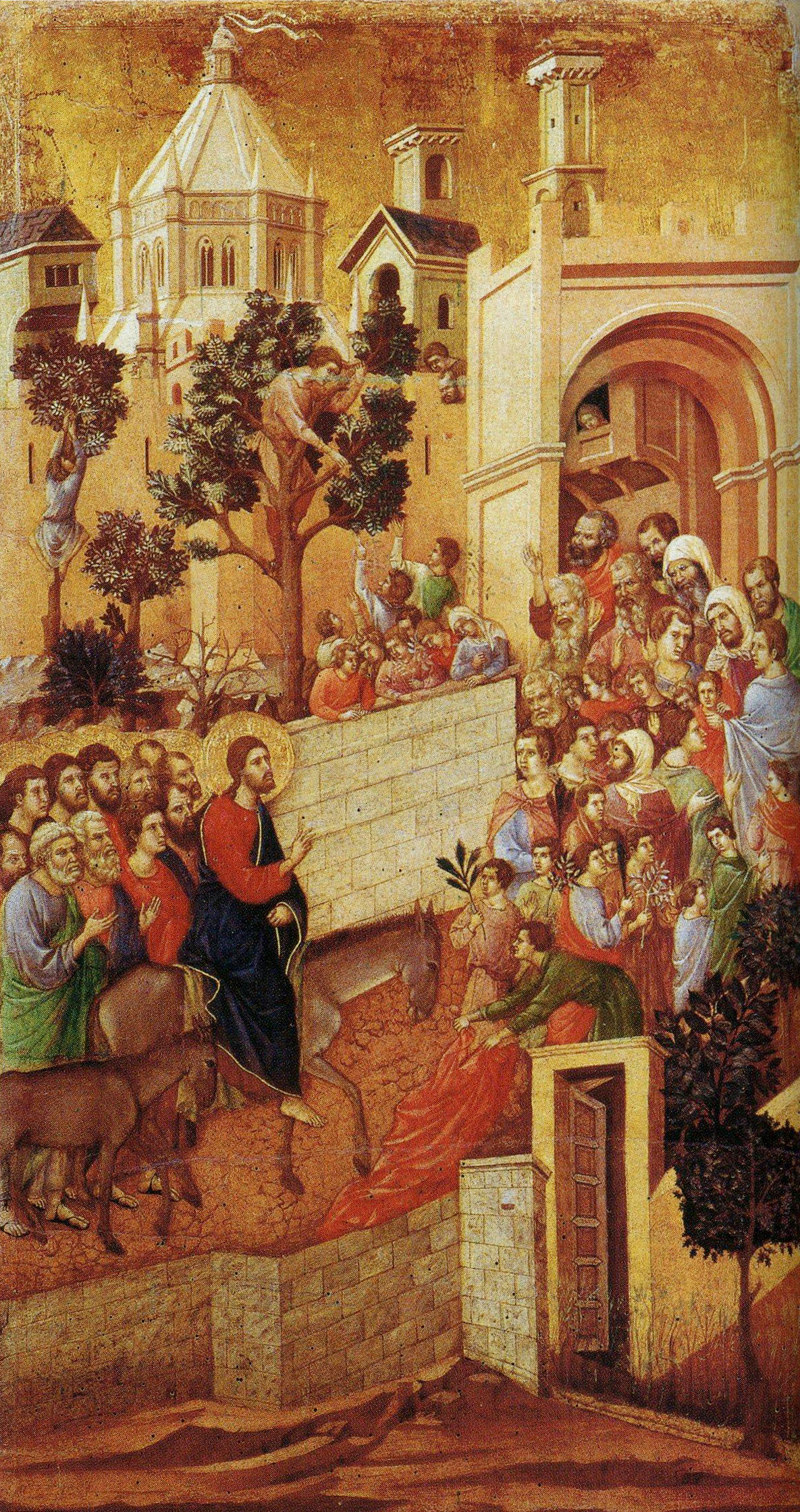

In the Entry into Jerusalem, Dixon point out: “(T)here is a highly sophisticated manipulation of surfaces for a peculiarly devotional purpose. Objects and persons alike are defined in faceted surfaces that are angled against each other in a complex pattern that may remind the modern observer of the structured facets of cubism. But instead of the profound structural purpose of cubism, ordering is here a trap for devotional meditation. The glance of the spectator slides from plane to plane, back into the symbolic space to the temple, out again to the figure of Jesus, who is crowned by the temple yet reaches it only through the life of the city.

“Since the picture is full of allusions to the experienced world and the circumstances of our common life, the origin of our response is the awareness of this world. But appearances are embedded into the intensity of color structure and the complexity of spatial organization—the common life is transfigured into the uncommon life of a spiritual event. There is no weight to figures or tangibility to stone, so the holy event floats like a mystical vision; yet the entrapment of vision is so complete that the serious spectator cannot extricate himself front his participation in the event. Thus the icon to which Duccio is so closely linked is carried still farther away from its appointed task and into a distinctly Western vision. This is no longer the occasion for prayer or the instrument of prayer. It is itself an act of devotion trapping not only the conscience but the optical consciousness of the spectator into a singular act of involvement with the deepest structures of the faith. From this the worshiper returns into his own circumstances not so much better informed about the nature of the common life as prepared to see the ordinariness of things radiant with the faith.”

Comments welcome.