“If I create from the heart, nearly everything works; if from the head, almost nothing.”― Marc Chagall

In her 1948 essay, Chagall ou I’Orage enchante, (Chagall or the Magical Storm), the French poet and philosopher, Raïssa Maritain, discusses Chagall’s use of abstract form in his paintings: He does not avoid natural forms; he does not fly from them, on the contrary he makes them his own through the love he bears them, but by the same token he transforms and transfigures them, brings out and draws from them their own surreality, finding there the symbols of joy and life in their purified essence, their spiritual soul. . . . With no preconceived idea, through his art’s magic, through the liberation of his internal world, Chagall has created forms signifying a spiritual universe entirely his own.

Comments welcome

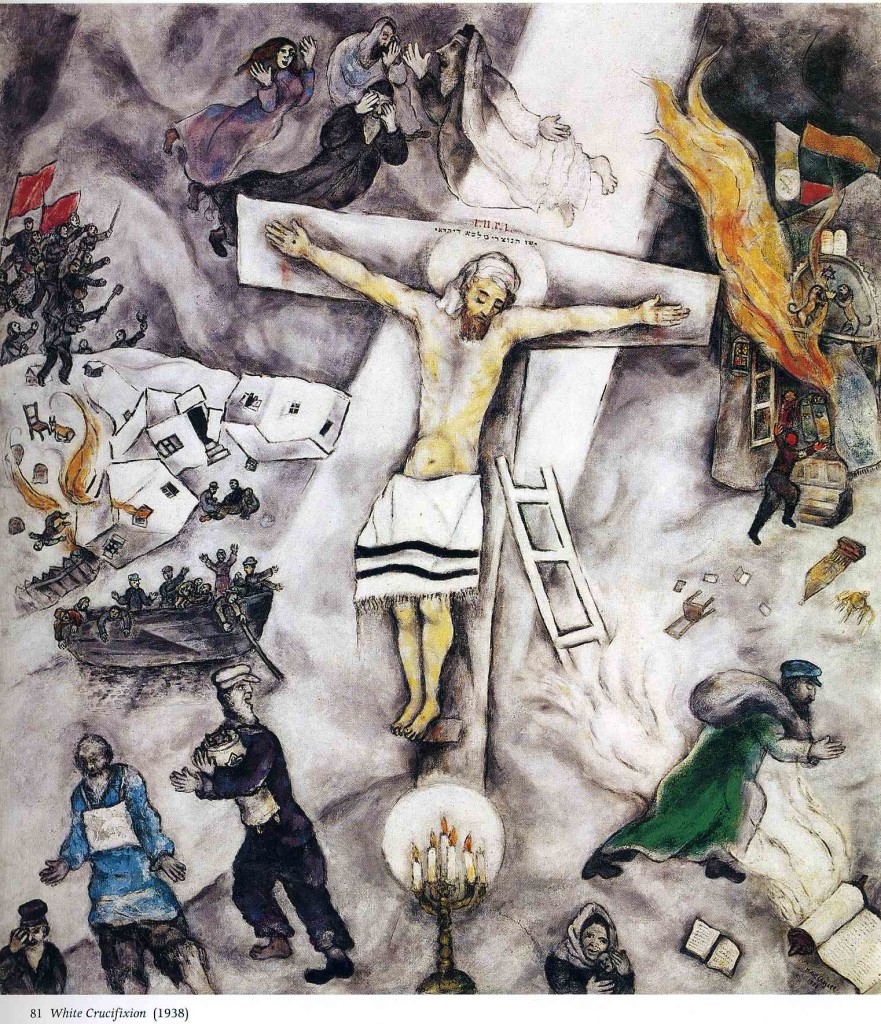

This is, of course, a painting that bears the weight of human violence–and the suffering that comes from it. This painting captures the horror of that story, with images of the “crucifixion” of the Jewish people surrounding the Crucified One–here, with a Jewish prayer shawl draped around his waist. And, at the top, the strange image of three who seem to be in flight from the violence (and, strangely, also in flight literally) being addressed by the old prophet Moses, perhaps. Is he encouraging them to become engaged, rather than refusing–as they seem to be–to hear, speak, or see what is happening below? Viewing it today, from the vantage point of the European refugee crisis, the little boat Chagall portrays finds an echo in the horrible plight of those trying to cross from the Middle East and northern Africa to what they hope will be a haven in Europe. But this hope, too, seems increasingly unsteady as the throngs continue to arrive and the patience and resources wear thin. Yes, this is a vivid image of Chagall’s “spiritual world,” but if so it builds on his very direct portrayal of the real, physical world in which this violence was enacted and continues to be enacted. Alas. And one small detail begs to be honored: Who will light the last candle on the menorah, to signify that the people will find their way through this wilderness of suffering?

Yes, so important to note. And thank you, Mark for making a very relevant current connection. Painted in 1938, the painting is believed to be Chagall’s response to the horrifying events of Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass,” an anti-Jewish pogrom carried out in Nazi Germany that same year. Another quote from Chagall, perhaps more relevant here: “When I paint, I pray.”